Today we inaugurate Pick Six, a semi-regular column where a DtHL writer picks six movies that share a common thread and briefly discusses their merits (which is essentially a fancy way of saying that Dim the House Lights will be doing the occasional listicle now). This first entry will focus on six great (or at the very least, great to me) feature-length animated films from the 1970s. Obviously, this is not an exhaustive or definitive list by any stretch of the imagination, but consider all of the following titles as personal recommendations.

Belladonna of Sadness (Eiichi Yamamoto, 1973)

Between 1969 and 1973, Mushi Productions, headed by legendary mangaka Osamu Tezuka, produced three adult animated films in the hopes of siphoning in some of that sweet pink-film money. These films are known as the Animerama Trilogy, all of which were either directed or co-directed by longtime Tezuka associate Eiichi Yamamoto. Belladonna of Sadness was the last of these films to be released, and is the only one to not have Tezuka on board as writer or director. The end result was an erotic psychedelic riff on the story of Joan of Arc that is equal parts avant-garde animation and Axis: Bold as Love-style graphic design. The film sputters when it tries to make any kind of sociological point about the loss of innocence or the corrupt nature of power, but it is so magnificently hypnotic and ornate the rest of the time that it trumps all of the weaker parts. Sadly, this one-of-a-kind head movie is out of print, but there are copies floating around.

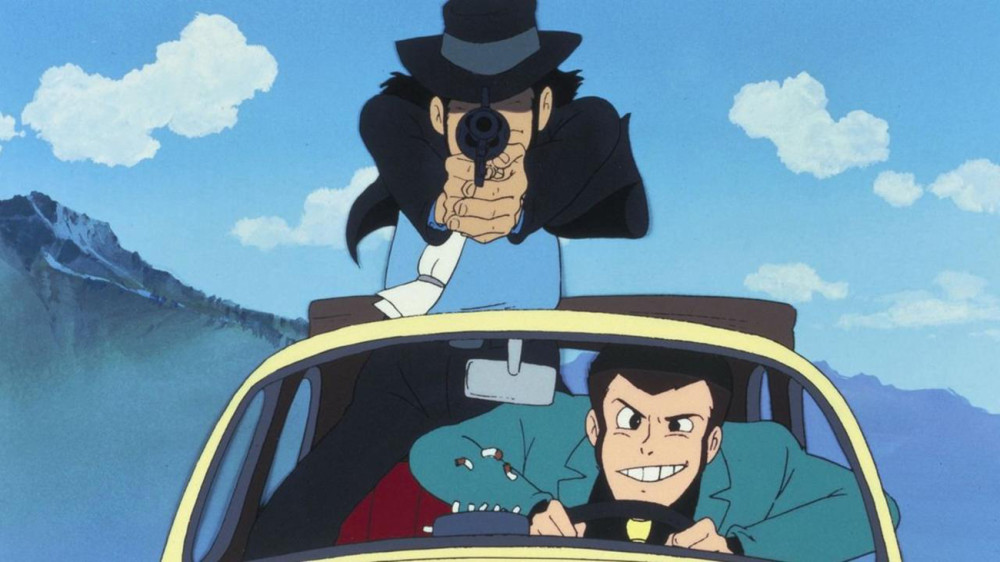

The Castle of Cagliostro (Hayao Miyazaki, 1979)

Hayao Miyazaki’s feature-length film debut as director was this contribution to the Lupin III media juggernaut, of which he was already a part of as a TV director. By the time The Castle of Cagliostro was released, Monkey Punch’s gentleman thief was already in his the middle of his second manga series and his second TV incarnation. Even without knowing this, it’s clear that this movie, a crackerjack caper involving a legendary counterfeit currency is very much unlike Miyazaki’s later films. Given the tonal constraints of the media franchise, The Castle of Cagliostro winds up being Miyazaki’s most cartoonish, action-packed, and violent film in his decades-long career; the film starts proper with a wild extended car chase and ends with a climax in a chapel is equal parts John Woo shootout and Satanic black mass. Still, even this early on, there are Miyazaki touchstones in place; gorgeous backgrounds, sumptuous architecture, and small moments (a shot of a field or of water hitting the shore) that break up smaller actions.

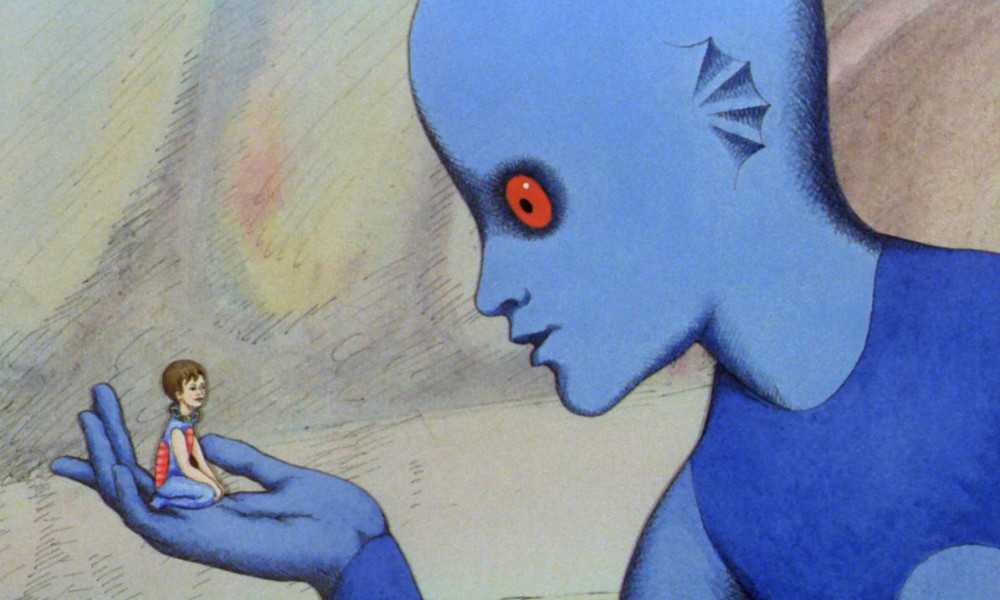

Fantastic Planet (René Laloux, 1972)

Adapted from a novel by cult French sci-fi writer Stefan Wul (who wrote 11 of his 12 novels between 1956 and 1959), Fantastic Planet was the first full-length feature by cult French animator René Laloux. Over the course of his career, Laloux kept returning to stories about oppressed groups with the cunning and will to overcome totalitarianism and assimilation. Here, the role of the downtrodden is filled by the Oms, a small race of human-like beings living in constant fear of the Draags, a race of blue-skinned humanoids that are heavy into psychic bonds and ritual meditation. The film trades in soft-SF psychedelic, yes, but it is also surreal, thanks to the contributions of cowriter/artist Roland Topor. The designs of the various creatures and landscapes of the film are truly inspired, trading in a minimalist kind of choppy nightmare imagery. The film is underpinned by an amazing acid-jazz score composed by former Boris Vian sideman Alain Goraguer. Fun fact: in 1982, Laloux would go on to direct Time Masters, an adaptation of another one of Wul’s novels, with the help of legendary artist Jean “Moebius” Giraud.

The Lord of the Rings (Ralph Bakshi, 1978)

Before Peter Jackson took a crack at it in grand fashion, American animation’s enfant terrible Ralph Bakshi adapted the first 2/3 or J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. At this point, Bakshi was known his blunt-force caricatures of the counterculture and urban life in general (the unpleasant Fritz the Cat, the much-lauded Heavy Traffic, and the brutal blaxploitation riff Coonskin), he made a transition to fantasy in the mid-70s. Bakshi was as visually inventive and ambitious as animators come: he was pioneering in the use of rotoscoping, using filtered live-action footage as a surreal counterpoint to his broad comic art style. This is highlighted in the film during the several superimposed battle sequences. It has the earthy, deliberate pacing of an epic, but with that comes the inevitable structural bloat. That said, it’s still a great fantasy adventure film, grand in ambition and sincere in execution. Also, this is probably the most 70s film on the list by virtue of it having been written by Peter S. Beagle, the author of The Last Unicorn.

The Rescuers (Wolfgang Reitherman, John Lounsbery, and Art Stevens, 1977)

By the time The Rescuers was released in the summer of 1977, Walt Disney Studios was in the middle of a critical and commercial downslide they wouldn’t snap out of until 1989. While the studio was already recycling animations and otherwise cutting costs (their early-70s movie The Aristocats and Robin Hood share some rather striking similarities), The Rescuers actually benefited from it. For one, it was the studios most textured film in fifteen years, and the closest the studio had to to that point to being “gritty.” The story, adapted from Margery Sharp’s series of children’s books, feature two murine delegates of a UN-like organization sent to help a kidnapped child being held captive on an abandoned riverboat. It’s a surprisingly dark film, both in lighting and imagery (a tense scene involving a child, a sword, and a skull is one for the ages), and a great adventure film to boot, bolstered by some great voice work by Bob Newhart, Eva Gabor, and Geraldine Page.

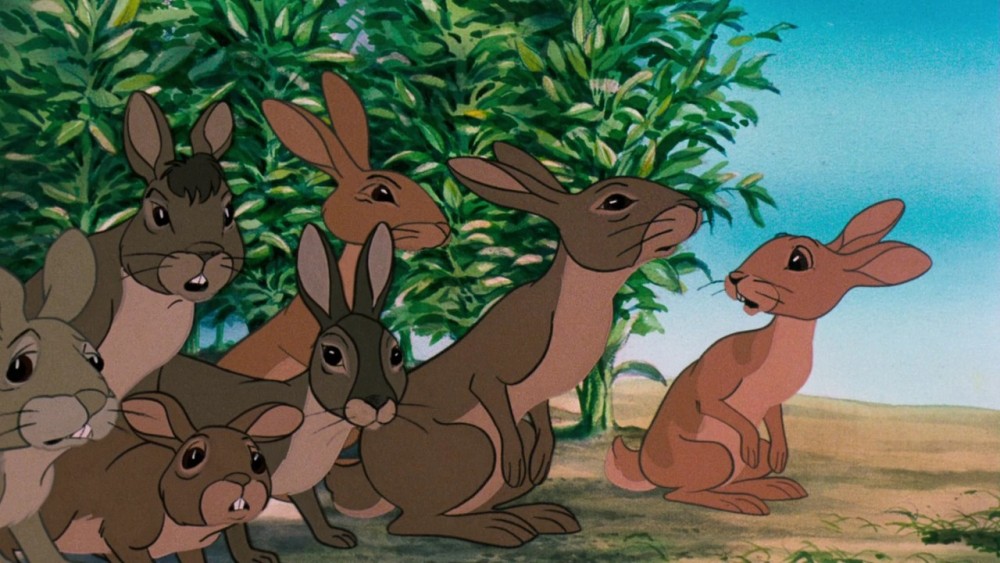

Watership Down (Martin Rosen, 1978)

Last month, I talked about Don Bluth’s The Secret of NIMH, and concluded that while commendable from a bucking-the-machine point of view, it didn’t have the charm of depth of the films it was trying to emulate. One of those films is Watership Down, the great British animated film that was recently introduced into the Criterion Collection. In retrospect, Bluth spent most of his career trying to nail down Watership Down‘s tone of old-school pastoral imagery and occasional, unflinching bleakness (right down the the comic-relief bird character, here played by Zero Mostel in his final role). What elevates Watership Down isn’t only the craft on display or its facility with a darker tone, but the fully-formed universe it depicts, right down to the creation myths and folk tales. There is a sneaky spiritual streak the permeates the film that ultimately makes it that much more resonant; while The Secret of NIMH merely addresses notions of heroism and leadership in the context of collective myth, Watership Down actually engages with them in a very raw, emotional way. It also features some breathtaking abstract, expressionistic animated passages helmed by John Hubley, who was slated to direct the film before sadly passing away in 1977.

Derek

Derek

Isabelle

Isabelle