Hayao Miyazaki has spent the bulk of his career as a coming-of-age fabulist, using light fantasy as a way of exploring the changes younger people go through as they mature. In his maybe/maybe not swan song The Wind Rises, Miyazaki shifts his attention from childhood to adulthood, where the exuberance of wonder and discovery get tempered by external forces. Maybe it’s because it’s a more adult film in tone, dealing in its own way with the Japanese war effort, but it’s also Miyazaki’s densest film in a walk, juggling disparate tones and moods nimbly while still retaining political bite.

The film is a biopic of sorts, chronicling the semi-fictionalized life of Mitsubishi engineer Jiro Horikoshi, who designed aircraft used by the Empire of Japan during World War II. The film paints him as a dreamer, an idealist, and oddly, a pacifist. It’s hinted that the film’s version of Horikoshi considers the Japanese participation in the war a futile endeavour (something he shares with his real-life counterpart), and he laments that airplanes, objects of beauty and grace, are used to senseless slaughter innocents. It’s an extreme metaphor for artistic compromise, one that’s politically dubious if you think about it for too long, but one that rings deep metatextually. In the original Japanese version, Jiro’s voice is provided by Hideaki Anno, creator of Neon Genesis Evangelion, in the role of the creative who sees his vision compromised by forces beyond his control. Between Miyazaki, Anno, and Horikoshi, there are three separate battles with the creative process going on at once.

The Wind Rises plays like a companion piece to Miyazaki’s 1989 film Kiki’s Delivery Service. Like in that movie, the protagonist deals with the joy and frustration of the creative process. But where Kiki was more concerned with the the internal, personal factors with regard to creativity (mostly the elusive nature of the creative knack), The Wind Rises takes a look at how those same impulses get curbed in a professional setting. The purity of an idea gets mutated by any number of outside factors; time, money, orders from on up. The characters repeatedly profess their admiration for design and craft, despite knowing full well that these very machines will be used to rain fire on civilians. Therein lies one of the remarkable complexities of the film: that an idea or a thought is always purer than where it ends up. An idea becomes corruptible when it starts to exist.

This is a movie that juggles a lot of tones. Beyond the Creative’s Dilemma angle, Miyazaki tosses in war-time paranoia, childlike wonder, and full-on melodrama. The latter of which is strange, since the Jiro/Naoko romantic arc was 100% fabricated for the film. Not that I would hold this film to the same standard that I would a regular biopic. If I did, I’d surely object to the presence of a completely fabricated love interest. But as it stands, the romantic arc adds to the film’s thematic richness; it’s another case of an idealistic vision (i.e. a home and a family) being doomed to fail.

This extends into a further treatise about the inherent frailty of human endeavor in general. Not even fifteen minutes into the film, Tokyo gets razed by the twin destructive forces of Earthquake and Fire. Planes crash and burn into piles of twisted metal. Even interpersonal relationships are strained by time, distance, paranoia, and disease. Ultimately, the only pure, ironclad things in the universe are ideas and dreams. Everything else has obsolescence built into it. Heavy stuff for this kind of movie, but the film’s charming artistic touches sweeten the pill.

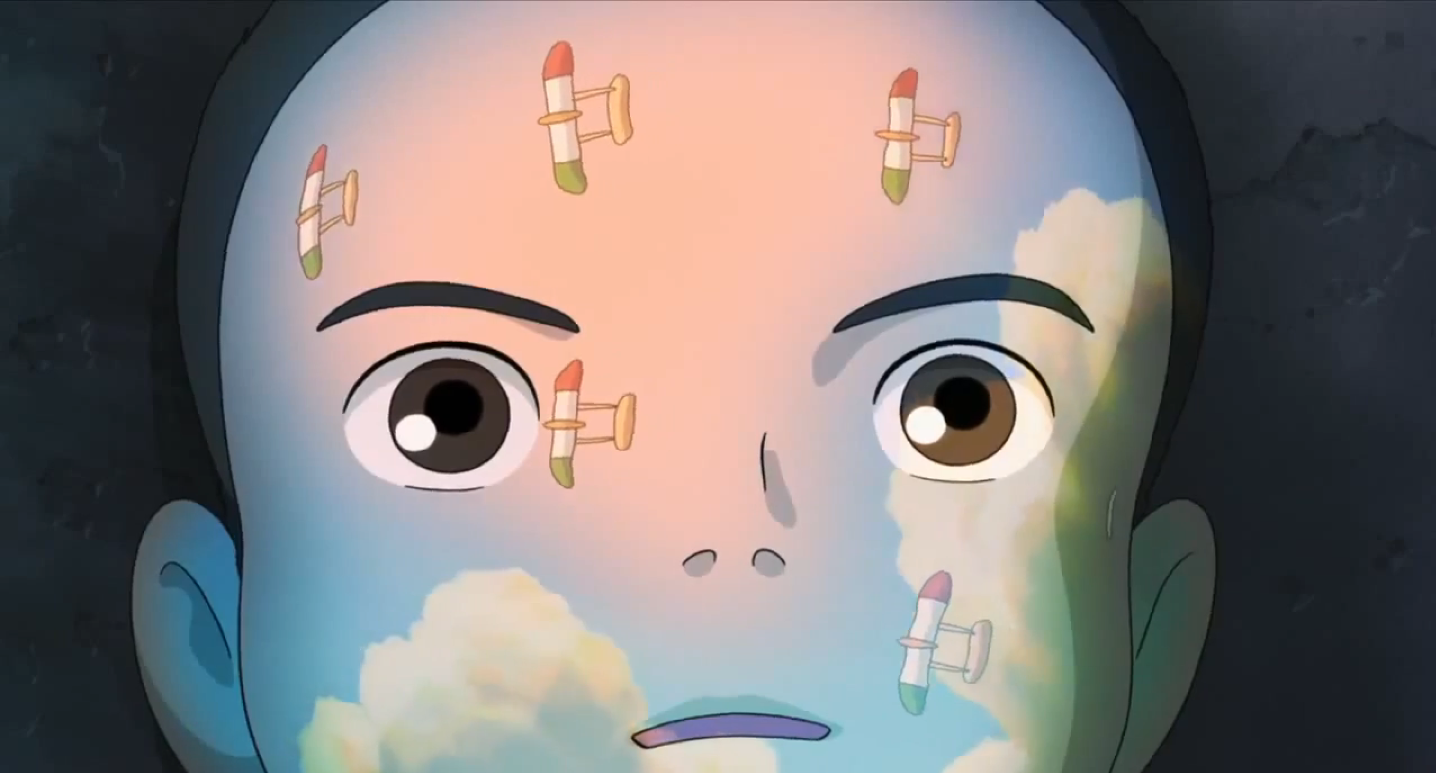

As expected from a Miyazaki film, the craft on display is first-rate. Impressionistic displays of the Japanese countryside collide with detailed depictions of urbanity. The early 20th century versions of Japan and Germany feel like real, lived-in spaces. The film’s dream sequences give a chance for Miyazaki to flex his animator’s muscle in interesting new ways; bare plane fuselages react to the elements in real time, baroque flying machines lumber towards flight, and, in one of the most striking images of the director’s career, a speedily-working Jiro plummets to the earth at a flaming desk, schematics flying every which way.

While the film’s scope allows Miyazaki’s animation to run wild (and the film is at least 50% bravado animation sequences involving planes), his is still a cinema of small gestures. Seemingly innocuous actions like pulling a drag from a cigarette or sketching out the arc of a mackerel bone pull an interesting double-duty. They draw attention to the skill of the craft on display (both the animation and the in-universe engineering), and give tiny moments incredible narrative depth, like each small gesture matters. Though a part of me wished that the movie would have taken a hard left into Zizek territory and engaged with the responsibility we have towards our dreams and ambitions, I am thoroughly enthralled about what I’m left with: a magnificently knotty roman-à-clef about being an artist inside a business.

—

The Wind Rises is currently playing in limited release in North America.

Directed by Hayao Miyazaki; written by Hayao Miyazaki; adapted from the comic Kaze Tachinu by Hayao Miyazaki; starring Hideaki Anno, Miori Takimoto, Hidetoshi Nishijima, Masahiko Nishimura, Stephen Alpert, and Morio Kazama; 126 minutes.

Derek

Derek

Isabelle

Isabelle