To inaugurate this new tape-centric feature on Dim the House Lights, I’ve chosen to talk about the hit 1988 comedy A Fish Called Wanda. Now why would I talk about this movie in a the context of a VHS column, you might ask? You may very well have a point; A Fish Called Wanda has had ten different home video releases in the last decade (seven on DVD, three on Blu-Ray, which is overkill by any metric). I could have easily rented this from the comedy section of my local video store and experienced it in full 1080p glory. But the purpose of DDVHS isn’t so much to view catalogue stuff in shiny new editions. That’s what the regular reviews and essays are for. The column isn’t even a platform to review VHS-only titles, because (a) I’m not that cool, and (b) I don’t have the time and resources to be scouting for VHS-only gems. Ideally, though, this column will be a small chronicle of what people get rid of: every single one of the titles covered here will be purchased at a thrift store for a single Canadian dollar. But hopefully, and this is my main ambition with this feature, DDVHS will also be an experiment to see how format affects filmic texts. For some weird reason, even with the glut of sharp, extras-packed reissues, some films simply play better on VHS.

I’m surprised that it took me this long to tick A Fish Called Wanda off my watchlist considering the tremendous talent of the people involved. I find John Cleese to be an exceptionally funny person, both in the context of Monty Python and all by his lonesome. He wasn’t the best straight man among the Pythons (that distinction goes to the late, great Graham Chapman), but did excel at playing po-faced, uptight authority figures. Archie Leach, Cleese’s character in the film, is the perfect portrait of stuffy, repressed upper-middle-classdom, complete with barrister wig and unsatisfying, low-wattage-glow marriage. Cleese also excels at frothing neurotic rage (see: Basil Fawlty), and though he wrote a character for the film that fits that mold, the performance ended up being handled not by him, but by Kevin Kline, and with remarkable verve at that.

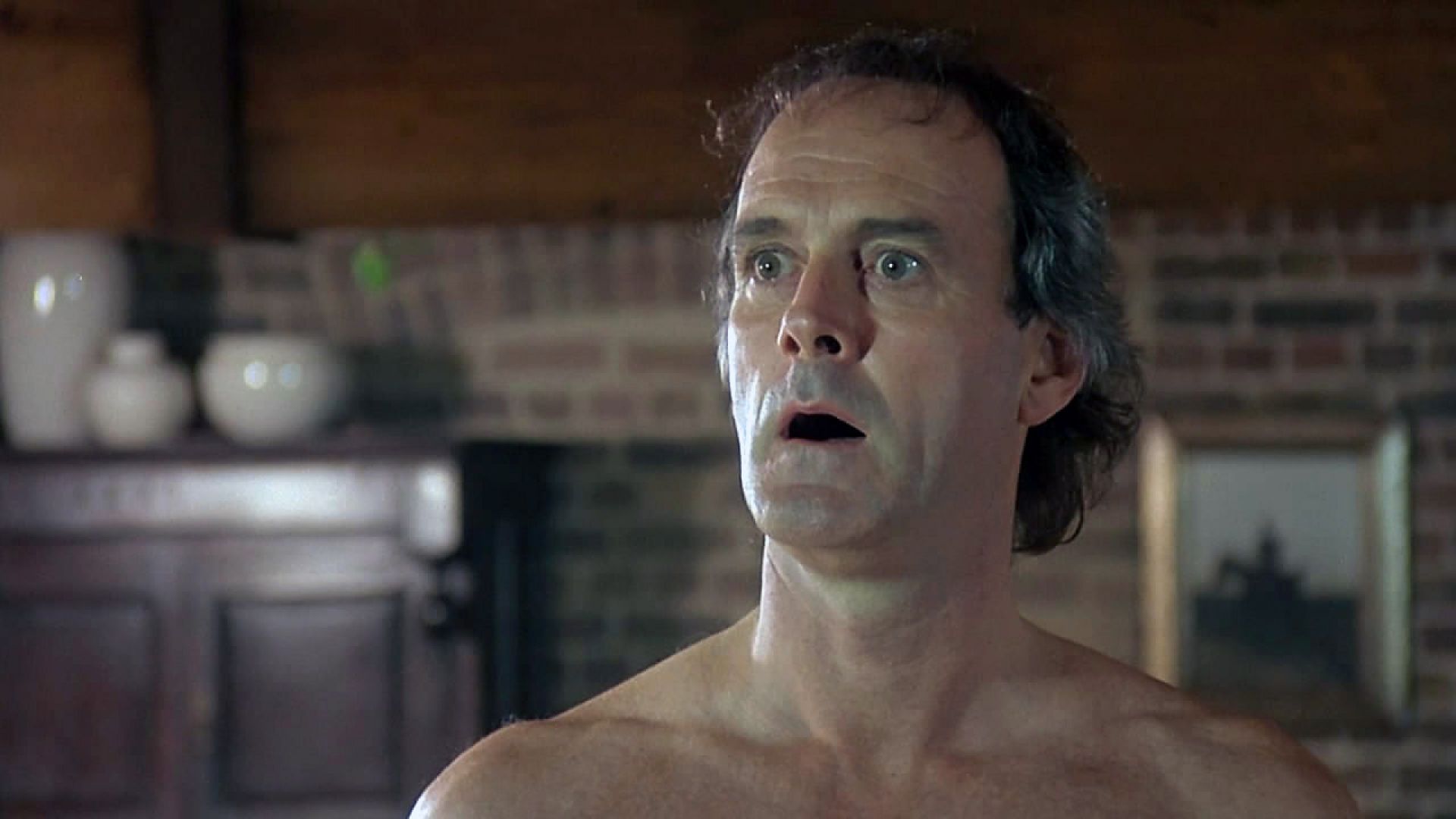

In fact, A Fish Called Wanda’s main draw is Kline’s deliciously weird portrayal of sociopathic ex-CIA agent Otto West, a character seemingly conceived as the physical embodiment of Cleese’s own maxim (by way of David Dunning) that some people are “so stupid that they have no idea how stupid they are.” West seems to live in his own personal fantasy world where he’s a badass thief/Buddhist/ladies’ man, but the illusion immediately begins to crumble the second someone lets on that they think he’s dumb (if the movie has a thematic through line, it’s the illusory, interchangeable nature of personas). He doesn’t help his own case much; he dicks around, smells his armpits, throws tantrums, and yells “asshole” in the most obnoxious way imaginable. Great American thespian that he is, Kline performs with admirable theatrical zeal, and it’s a thrill to see that kind of power devoted to absolute silliness. But the most glorious thing about Kline’s uniquely bugged-out performance is that it netted him the Academy Award Best Supporting Actor, which in and of itself is nothing short of a miracle. A performance this eccentric and flat-out funny wouldn’t even get nominated 25 years on.

Actually, the whole cast in this film is rock-solid: Jamie Lee Curtis is excellent as the femme fatale figure with a marked weakness for non-English languages, and Michael Palin works some of the old Python magic as a stuttering hitman with a fondness for animals. But this being the brainchild of Cleese, a sketch comedy veteran, and Charles Crichton, a director known for his old-school Ealing Studio comedies, this is mostly a gag-based affair. A Fish Called Wanda is an enthralling, eminently likable synthesis of Pythonesque lunacy (the running gag involving Palin and an elderly woman’s dogs feels straight out of the Flying Circus playbook) and breezy, mid-century comedy. Crichton has an unobtrusive style that gives the actors and screenplay room to breathe, but manages to keep the proceedings from becoming visually dull. Often, all it takes is a zoom or an odd angle to liven up a scene, since the performers are already doing so much of the heavy lifting, and not just with the jokes. There’s also a surprising amount of physicality on display: Cleese’s twinkle-toed striptease while speaking in Russian, or Kline’s lotus position/ninja roll/stealth pose combo.

So does it look okay on VHS? Sure, in the same way that the Flying Circus would look fine on VHS. Comedies, especially nowadays, tend to be formally bland, and even the more adventurous ones wouldn’t be greatly limited by a 4:3 aspect ratio. The only real thing that suffers in the adjusted format are the opening credits: both the actors and the credits are oddly blocked as they roll. What isn’t affected is the quality and the pacing of the gags, and the brilliant delivery thereof. The integrity of the diegetic world isn’t compromised by the medium because of said world’s verisimilitude. As we’ll see next time, when the world is more “artificial” and requires more suspension of disbelief, the consideration of format texture becomes much more important.

—

Directed by Charles Crichton; written by John Cleese and Charles Crichton; starring John Cleese, Jamie Lee Curtis, Kevin Kline, and Michael Palin; 109 minutes.

Derek

Derek

Isabelle

Isabelle