Through the translucent letters of the main titles, you can see bodies moving, running, and when it cuts away to the streets of London, those bodies roam free form. They run, filled with joy and maybe a little aimlessness. Though Carlo Di Palma’s color palette leans towards blue and green, the colors on these swinging kids’ clothes pop, almost sickeningly. They run around, without much explicit object, and their clamor and din is reminiscent of the opening of Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night, the opening of which features a swath of young people chasing after the Beatles. Here, too, these folks chase after something as elusive as some sort of capitalistic fever dream.

But Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up quickly descends into nightmare, as Thomas (David Hemminigs), a photographer, begins to lose the ability to delineate between the image and reality, the fantasy and the real, the tangible and the intangible. Blow-Up becomes positioned as a film that’s so disillusioned with the hip London of the 1960s that its main characters literally disappears off the screen by the end of the film, consumed by his culture’s own consumerism and wanton desires.

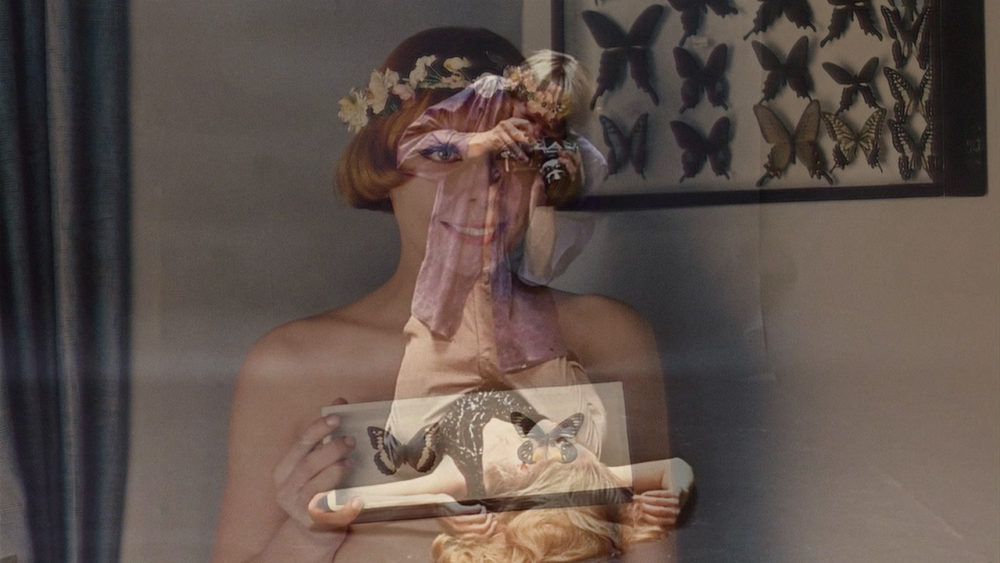

So much of the film is about the mediations between the real and the image, and it’s rare that we see Thomas without a camera, or at least without some sort of barrier between himself and the moment he’s capturing. His work as a photographer, mixing fastidiousness and free from eroticism, places his models in ways where they are either literally bifurcated by glass or by set or where the lens of the camera serves as the mediator between them. He mixes business and pleasure without dichotomization, also mixing the image and the real, and distinguishing the two from one another for him becomes impossible.

Thus, the alleged murder that he captures on film is just another element of this, another aspect of his being emblematic of a culture that would grow to be subsumed by capitalism and a form of consumerist ideology where compartmentalizing between reality and fantasy would no longer become necessary or important. As he develops the film and prints it larger and larger, Thomas, ironically, cannot delineate between the image and reality because they have been conflated.

In that way, Blow-Up’s gender dynamics are connected to this consumerist ideology, linking it to these patriarchal values of female submission. It is always Thomas that is behind the camera, capturing his female models performing sex and sexuality. Though intimacy is not a main objective of the film’s exploration, Thomas’s very lack of being intimate suggests that the London of the 1960s prevented that very act, that the photography almost offset any kind of authenticity when it came to love and romance. In addition to this, the capturing of women on film, or as the song goes, girls on film, suggests a lack of agency and autonomy, given the way that the culture had oriented itself around the very populism that both Blow-Up and A Hard Day’s Night depicts.

If anything, that means that Blow-Up implies that men can be consumed by this nightmare, not totally unlike women.

However aesthetically and stylistically different Věra Chytilová’s Daisies is, it doesn’t come completely from a different angle. Its nightmarishness is only relational to the anarchic antics of its main characters, Marie I (Jitka Cerhová) and Marie II (Ivana Karbanová), two young women who are interchangeable inasmuch as their desire to dismantle the capitalist heteropatriarchy itself. It’s framed as whimsical, but it’s as diabolically wonderful as Blow-Up’s unsettling deconstruction.

Where Blow-Up deconstructed patriarchy, Daisies seeks for its destruction. The turning gears at the beginning juxtaposed against the images from WWII and the percussive music present an unusual, cleverly sarcastic and ironic version of the whimsy that will be to come.

In many ways, Daisies is exhausting because of how relentless it is, in its visual style as well as its illogical leanings. When both maries go to dinner, they play the game and within the parameters set by social propriety, but they will soon have none of that, playing with their food, creating complete anarchy within very bourgeoisie contexts. There’s the invocation of Chaplin and Keaton, but with an intentionally fiendish objective. Fiendish in a good way.

Narratively, it almost sets the blueprint for shows like Broad City and films like Frances Ha, works of persona-swapping, female friendship, and landscapes where men exist relationally to women, instead of the other way around. Thus, to have a film so dominated by women and the feminine, for that kind of power to be placed above, is both fever dream and nightmare, the latter for the mainstream.

The two Maries swing from the chandelier, and Sia would be proud. But under the guise of fun and flamboyancy, Daisies is as cynical and nihilistic about the realities of womanhood as any film, the film ending with the two, after a long feast, wrapped in paper, lying beneath a totem of middle class life, only to be destroyed by it.

However, Blow-Up’s deconstructionist route and examination of mediation only goes so far before it comes stagnant in its pace, brooding in a way that ends up undermining part of its thesis. It becomes almost too invested in Thomas to somehow find a modicum of redemption, either for himself or for the culture he lives in, and while the film’s nihilistic ending is pleasurable, it falls short in comparison to that of Daisies. Daisies is able to act with complete joy and complete anger, the two swinging back and forth, vacillating endlessly, making exchanges like a persona swap. It is that very kind of technique and approach which feels subversive and fresh, even fifty years later.

The winner: Daisies

—

Blow-Up; directed by Michelangelo Antonioni; written by Michelangelo Antonioni, Edward Bond, and Tonino Guerra; starring David Hemmings, Vanessa Redgrave, and Sarah Miles; 111 minutes.

Daisies; directed by Věra Chytilová; written by Věra Chytilová, Ester Krumbachová, and Pavel Juráček; starring Jitka Cerhová, Ivana Karbanová, Marie Češková, Jiřina Myšková, and Marcela Březinová; 76 minutes.

—

Kyle Turner (queer cis male monster, he/him) is a freelance writer, editor, and transcriber, and, if John Waters is to be believed, a good dancer. He began writing on the internet in 2007 with his blog The Movie Scene. Since then, he has contributed to Esquire, MUBI, Playboy.com, Flavorwire, Little White Lies, The Film Stage, Film School Rejects, Under the Radar, and IndieWire’s /Bent. He is studying cinema at the University of Hartford. He is relieved to know that he is not a golem.

Derek

Derek

Isabelle

Isabelle