Nearly every film buff has their own favorite movie that never got made. The history of film is littered with projects that might have been, could have been, but never were. It’s the nature of the business for these scraps to pile up; the amount of produced scripts absolutely pales in comparison to the number of great scripts that ended up in someone’s garbage can, victim of an executive whim, poor timing, or simple bad luck. It’s a fun diversion, entertaining yourself or your friends for a bit imagining what this movie could have been; in the light of imagination, we all envision our pet failures as having changed cinema, as having been unrealized masterpieces, ignoring that virtually no one who’s ever worked in Hollywood has a perfect track record.Jodorowsky’s Dune explores one of cinema’s most legendary missed opportunities, and it hits the same pleasure centers as these aimless discussions do, and expertly so. But the reason it so constantly fascinates is that it has two brilliant tricks up its sleeve: one, we get to hear straight from the key players how it all went down, and two, we’ve got pictures of the ship when it was soaring so incredibly high.

The main interview subject, Alejandro Jodorowsky himself, is an egotistical little sunbeam, lighting up entire subjects by virtue of his own unbridled enthusiasm. Without a director like him, the film would sag under the weight of its declarations; “greatest film never made” is a hard pill to swallow until Jodorowsky comes onscreen and makes you believe it. His emotion carries it, as we see his massive ambition collide with crushing failure. He’s open and honest throughout, showing the real person behind this legend and giving us something to connect with. When he talks about his joy at David Lynch’s artistic failure with his own version of Dune, it’s hard not to appreciate this moment of humanity the same way he does, not as noble, but as true. Along with him, nearly all of the major players in the film that never happened show up to tell their story, from producer Michel Seydoux to Alejandro’s son Brontis (who was meant to star) to legendary artists Chris Foss and H.R. Giger, Through them, we hear how this film evolved, grew, and blossomed, and ultimately how it was cut short, victim of a studio unwilling to take such an expensive risk on Jodorowsky, a filmmaker best know for making surreal, freak-out classics like El Topo and The Holy Mountain. They tell the story like we don’t already know the ending, and it allows you to get caught up in it, waiting for the next animated storyboard or breathtaking painting with anticipation and excitement.

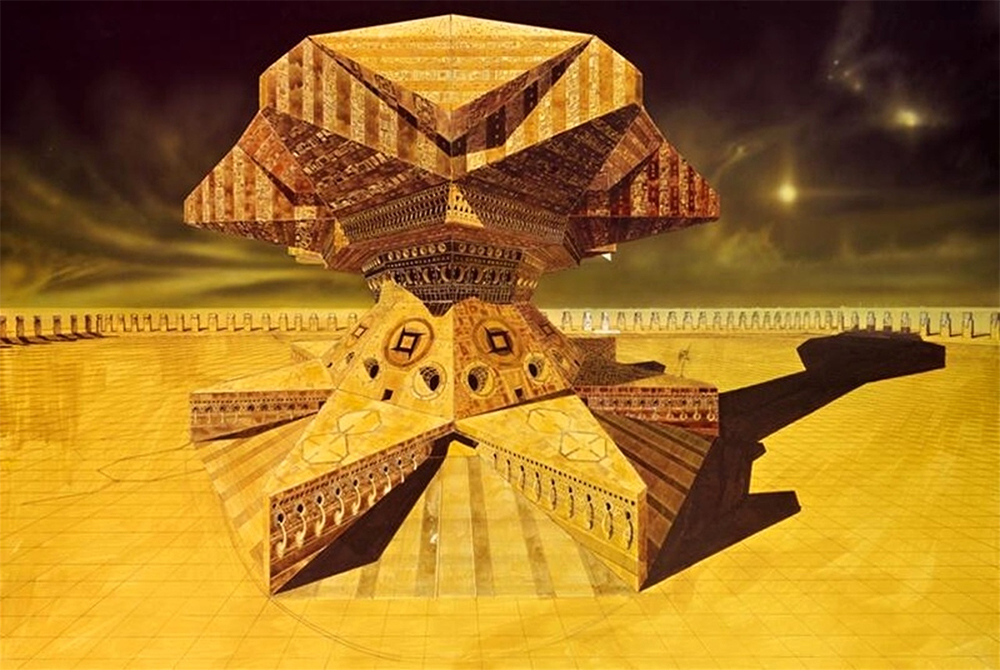

Those paintings, taken from this massive book of Jodorowsky’s containing the complete storyboards and pre-production design, originally made to show to all of the major studios, are the true star of the film. To see Chris Foss’ painting of a pirate ship spilling spice out of its hull is to feel wonder; to see Giger’s vision of a massive palace built as a monstrously obese human form is to feel dread. These moments took my breath away; these are masterpieces of science-fiction visual art, and your mind does somersaults imagining how they would have looked in the film, how they would have been constructed. I saw Jodorowsky’s home-spun effects merge with the grandiose scale of Star Wars’ most incredible set pieces, and I saw it all come to life in my mind. It was a beautiful thing to behold, if only in my imagination, and if only for an instant.

If there is a purpose to Jodorowsky’s Dune besides its interest to film buffs and sci-fi nerds, I think it’s that. Jodorowsky will never make Dune; even if, somehow, he had the chance, the film made now would not be the same film as then. Hell, the film then would not have been the film Jodorowsky’s Dune told me it would have been anyway. No film could be what the legend looks like in our minds, on the page, planned out so perfectly, never put into motion. But we can see it now, briefly; we can catch glimpses of it, beautiful glimpses, as we hear the story of its rise and fall, and we see pieces of the dream flow into the real world, changed and moved but still recognizable. It’s an ideal that seeps into the lives of those who believe in it, it’s the pollution sullying up the clean world of proper sci-fi, and bless it so. When the credits roll, it’s hard not to agree when Jodorowsky says that dreams can change the world.

—

Jodorowsky’s Dune is playing in select theaters, including the Miami Beach Cinematheque as of June 7th.

Directed by Frank Pavich; starring Alejandro Jodorowsky; 90 minutes.

Derek

Derek

Isabelle

Isabelle