Or, the Politics of Slim Pickings and the Scenic Routes to Cinephilia

Yesterday I watched Casablanca for the first time. On the surface, that doesn’t seem like a major event, but consider the following. I’m 26 years old. I’ve been actively watching movies for the better part of two decades. I have five years of film-centric education under my belt. I have a master’s degree in the field. Hell, I reference Casablanca at the beginning of my god damn thesis in conjunction with Umberto Eco’s seminal cult film studies text “Casablanca: Cult movies and intertextual collage” (I don’t agree with a lot of it, but it’s basically the Rosetta Stone for how we approach cult films as a thing). Despite all of this, I have only just now seen Casablanca, as of maybe twenty hours ago.

Everyone has a watchlist with embarrassing entries in it, but mine reads like a Film 101 syllabus. The Godfather. Lawrence of Arabia. Battleship Potemkin. The Searchers. And those are just the four that come to mind right now. Vertigo and Star Wars were both on that list just a short time ago. So what does any of this mean? Well, nothing really, if you don’t buy into notions of a capital-c Canon. But most of us operate under the notion that certain movies are simply required viewing. Essentially, that you are in a way lacking as a cinephile if your personal filmography has certain specific gaps in it.

Now I realize just three paragraphs in that this discussion could easily fractal off into a million different directions and remain pertinent. There are the inherent politics of creating and curating a Canon, or the received wisdom regarding who is “qualified” to do such a thing, or the cultural capital we attach to certain movies or directors or genres. There’s the societal factors that lead a film to acceptance and acclaim, and the idea that we can divorce a film from its context to get to the meat of it (which is neoformalist hogwash of the highest order because a film is nothing without some kind of context to hold it together, but that’s another discussion for another time). But what I mostly want to talk about is accessibility, specifically about how cinephilia blossoms somewhere that isn’t a coastal arts haven, a bustling metropolis, or somewhere where movies aren’t put at an intellectual premium.

I come from a sleepy rural town in western Quebec, right on a secondary highway, about an hour and some change outside of Ottawa. When people think of Canadian film culture, they generally don’t talk about Ottawa, dwarfed by the twin cultural pillars of Toronto to the west and Montreal to the east. But the nation’s capital does the glorious bidding of the Cinema Gods in its own way; the Bytown Cinema is a great rep house smack in the downtown core, and the Ottawa International Animation Festival stands as one of the best places on the continent to get your toon on. I didn’t know that any of this was going on, and I wasn’t even an hour away.

Even if I knew someone who would have been down for multi-hour jaunts into Ontario and back, I probably would have been limited to what was readily available in my town. There were two video stores, three for a brief period of time. To my knowledge, there are currently zero in operation. And they weren’t exactly great video stores. Sure, they were all mom-and-pop joints, but they were crappy ones. If you were looking for anything beyond a recently-released studio effort, you were shit out of luck. Everything was either Action, Comedy, Drama, Horror, or Sci-Fi. There probably couldn’t have been more that a couple hundred titles, less so as video games started taking up more and more space. I understand that even by the late 90s and early 00s, the video store as cinematic oasis both beautiful and strange was already on its way out. But we made due, I suppose.

I know that my love of movies was my own because I didn’t inherit it from anyone. I didn’t have an in-the-know older sibling or a cool relative who would clue me in on movies I’d like (although my uncle did basically give me and my sister his VHS copies of Grease 2, Mannequin, and Howard the Duck, which we watched and loved, ‘cause what else were we going to watch?). My parents weren’t, and still aren’t, big movie people. The first time I went to the movies with my dad was when we saw Superbad together in 2007. I don’t remember ever going to the movies with my mom. It wasn’t ever really a thing for me to go out to the movies. Movies were things you rented to kill time at home because you didn’t have a car. Movies were things your mom bought for you at K-Mart when you were a kid. A consistent prop in my childhood recollections is the clamshell box for Disney movies released on VHS. But then I became a teenager, and wanted to buy movies for myself, but it was seen as a waste of money. What good is buying a movie when you’re already going to have seen it?

That was my experience with movies until my mid-teens: movies are product. They are to be consumed and digested once, and when the credits roll, they have performed their duty. They divert you for two hours, no need to mull them over, onto the next thing. Further compounding this idea that movies were just images to consume, thereby reducing them to a base capitalistic unit, was our local movie theatre: the gloriously mangy Cinema Lyn. Looking back, it was a glorified second- or third-run theatre, only playing the box-office giants of the recent past on its one screen. It was only open during the summer and fall, mostly because (a) kids and teens made up the vast majority of the audience, and (b) it didn’t make fiscal sense for the place to pay for the heating during the lean winter months. Video stores made things democratic, but within that democracy, there was a weird plutocracy at play that I didn’t manage to escape until, surprise surprise, I started making scratch of my own.

It took Pulp Fiction, Clerks and Crumb for me to realize that movie weren’t all the same. In their own way, those movies showed me that there was a history to consider, that there were different modes to operate in, that a filmic personality could be imbued within a certain framework, and that that said framework could be dismantled and re-assembled to thrilling effect. But this wasn’t until we entered the 21st century. My early cinematic heroes weren’t pioneering iconoclasts or master craftsmen. Case in point, I know that Steven Spielberg’s work shaped the way a lot of my peers see movies, but I didn’t see a Spielberg movie until I was well into my twenties, with the possible exception of Hook, which I don’t remember finishing. No, my cinematic heroes weren’t really outcasts, they were just… strange.

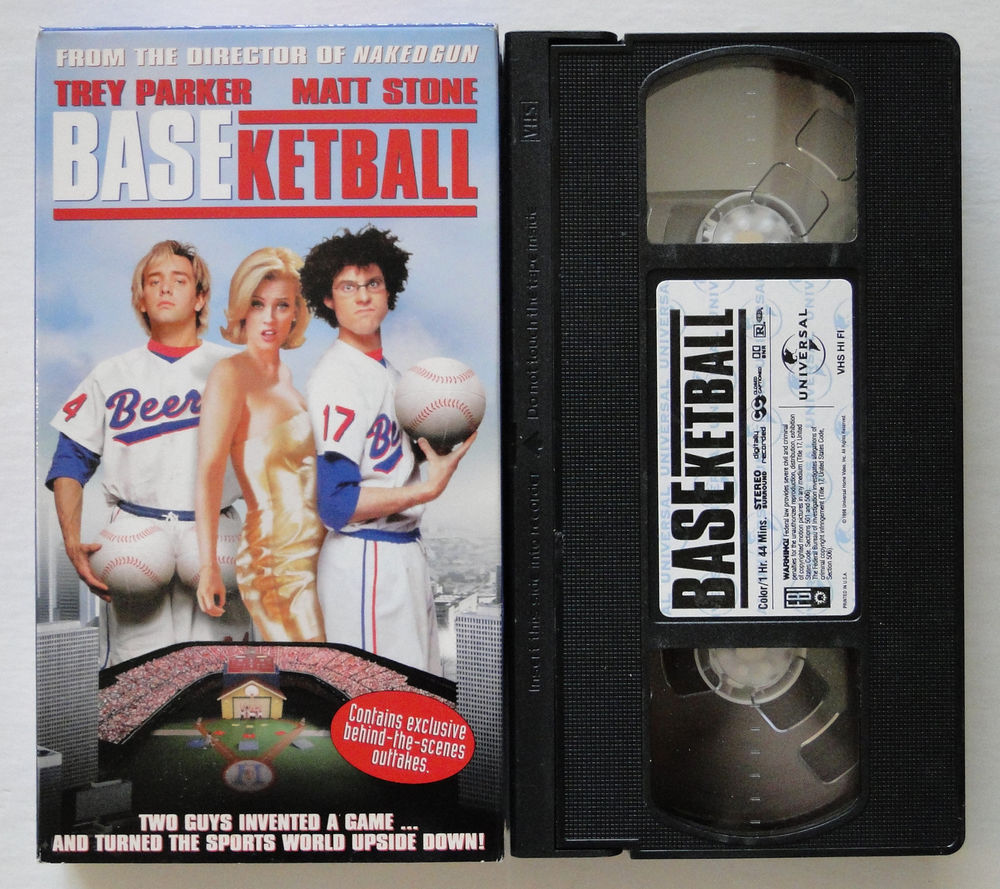

There were three movies I was obsessed with in early high school. I call them the Dad’s Farmhouse Trilogy, because I mostly watched them at my father’s farmhouse out in the boonies. There was Kinka Usher’s Mystery Men (I remember being intrigued by it because I recognized Hank Azaria’s name from The Simpsons), Norman Jewison’s Rollerball (culled from a list in an issue of Sports Illustrated; I was heavy into fake sports), but my favourite of the three was David Zucker’s BASEketball. I first saw it when I was 11, I was way too young, and I didn’t know a South Park or an Airplane! from a hole in the ground. But I loved that movie dearly (I was drawn to the idea of hybrid sports and broad comedy coming together, which tells you everything you need to know about yours truly as a young lad).

What I’m getting at is that since I was living somewhere where I wasn’t privy to a deep catalogue of movies; what I could have pored over and dissected QT-style was severely limited. As such, my early cinephilia feels stunted in retrospect, like it was trying to grow while being constrained by outside forces. My budding obsession with movies was basically the cultural equivalent of a lotus foot. Discovering specialty movie channels and IMDb and Ebert/Maltin movie guides certainly helped (this was how I first saw the aforementioned Rollerball and Vincenzo Natali’s Cube, still an all-time favourite and the ground zero for my love of both sci-fi and Canuxploitation). But even all these years on, armed with a degree in a city with more film festivals that I have phalanges, I feel like I’ve been playing catch-up ever since. Oddly, going to film school has accentuated my perceived cultural blindness. The driving political force behind what movies had priority to be seen wasn’t money or location anymore, but academia. I was in the precarious position of having done my BA in English, so I wasn’t privy to a lot of the canonical stuff freshmen watch. I went straight into niche interest territory. My cinematic baggage was vastly different from that of my professors and peers, and in an odd way, was wrong.

What I’m about to say sounds pompous, but it rings true, at least to me: every watchlist you build, every trip to the video store you make, every which way you consume a film is political in its own way. There’s a complex kind of intellectual alchemy occurring every time you pick a movie to watch, and how you actually watch it. For the first half of my life, I was “picking” from what was available to me, and I put that in quotes because there was some other guiding force making the decisions that wasn’t “I want to see this movie.” It was mostly “This is what my mom bought” or “This is what’ll be playing at the Lyn for the next two weeks and my buddies want to hang out.” Now that I live in a cultural hotbed in the Internet era, I have the opposite problem, but the same result. I have an embarrassment of riches to choose from and absolutely no way to cull it effectively. It’s like having a flashlight pointed at my face after spending nearly two decades in pitch darkness.

That said, I would much rather have the latter problem than the former, but I’m still fighting the bullshit notion that I should see some movies before I see others. I once had no chance to watch what was out there. Taking my sweet time with the Canon feels like the antidote to that, as if it’s my way of reading film history on my terms. Cinephilia, love of movies, right?

Derek

Derek

Isabelle

Isabelle