How’s this for a plot summary: David Bowie plays a humanoid alien who comes to Earth, exploits American patent laws to amass a fortune, and tries to build a spaceship to get back home. Getting in the way are rival corporations, the federal government, and all manner of earthly vice (pick your poison: sex, booze, TV). That’s the basic through-line of the film, but it doesn’t do justice its scope. In true 70s fashion, the wide thematic range of the film isn’t due to any kind of ideological restlessness. It’s because the universe of the film is so loosely-defined that what transpires could be about a million different things, and that raw allegorical power is its greatest asset.

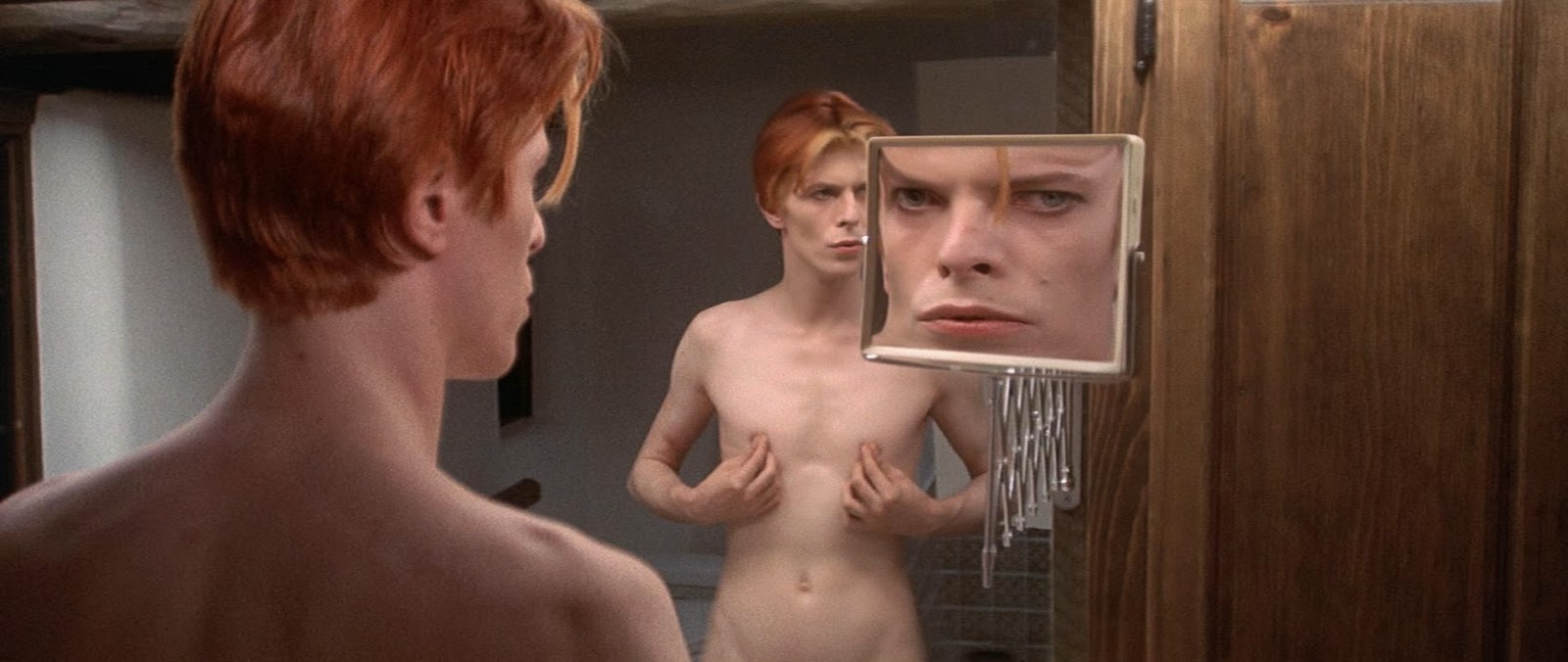

Nicolas Roeg’s bizarre sci-fi riddle is an oddity for many reasons, chief among those is the placement of the frail, coked-out Bowie front and centre. There’s a certain shrewdness on display here; Bowie had already built a career by channeling his inner alien, and his character in this film bears more than a passing resemblance to his contemporaneous Thin White Duke persona. Between all the emotional distance and curious sci-fi trappings, it often feels like we’re watching a The Wall-esque lamentation of what it is to be David Bowie. But while The Wall‘s imagery was as blunt as a billy club, the visuals in The Man Who Fell to Earth are mostly abstract and associative.

Roeg started off his career as a cinematographer and lensed his first two features, but his unique, colourful eye is plenty present even in his direction. The film starts off as a fairly standard wanderer tale, but grows most disjointed it progresses. We flash back to the visitor’s home planet (which mostly consists of a patch of desert with a monorail), solar flares and star fields superimposed onto the frame. Most of it is culled from the 70s sci-fi head film playbook, but it works as the approximation of an otherworldly consciousness.

The film gains steam as it goes on because it becomes clearer that since we’re following an alien creature, the laws of time and physics don’t always apply. It is implied that the alien can exist at multiple places in spacetime at once, and he also appears to be impervious to infection and aging. Still, he’s no match for the scourge that is liquor and ass. To the movie’s credit, it pulls off the “vice makes fools out of the best of us” angle without being preachy, using it more as a springboard to address broader ills. But it does so in a very elliptical way, focusing more on feeling than structure. I’m a great fan of the messy, jarring cinematic excesses of the 1970s, so I was fully on board with some of the hokier imagery, like Bowie yelling at a wall of TVs, ordering them to get out of his mind, or the revelation of Bowie’s true form and the ensuing panic from his lover. But beneath the surface-level weirdness is an earnest treatise on isolation, substance abuse, the difficulty of building and maintaining relationships, ethics, American exceptionalism, and just about everything else they make movies about.

—

The Man Who Fell to Earth is available on DVD and Blu-Ray from Amazon.

Directed by Nicolas Roeg; written by Paul Mayersberg; adapted from the book by Walter Tevis; starring David Bowie, Rip Torn, Candy Clark, Buck Henry, and Bernie Casey; 138 minutes.

Derek

Derek

Isabelle

Isabelle