Imagine the complicated lineage of the imagined catchphrase “just the facts ma’am” (culturally imagined to be from Dragnet, actually from a satire of Dragnet, and repeated in the film version of Dragnet which is also a satire of Dragnet the tv show) played out on a million television screens, piled on top of each other in a gargantuan and obscene mountain. Now imagine Rodney Ascher taking a wrecking ball and breaking that disgusting monument to objective reality down to size, and maybe you’re ready for Room 237 or The Nightmare (or his quite good short The S From Hell), because let me be clear: these are documentaries that don’t give a hot horse dump about the tangible, about the rational, about the things we can really touch with our own hands, put our fingers on. No, Ascher submits to the subjective credo, an idea that all reality can only be understood through imperfect experience. The Shining might be, in the eyes of a respected film critic, about loneliness, about work, about the ways the past haunts us even when we don’t realize it, and to someone else it might be about how Kubrick faked the moon landing. Toe-may-toe, toe-mah-toe, what’s the real difference? If we understand reality to be a collection of experiences (and, as best as I can tell, it’s a pretty clear view), the actual nature of any situation is unimportant; it’s the angle you look at it that matters.

So we find Ascher’s newest documentary, The Nightmare, in much the same space as Room 237; for those looking for a penetrating and informative glance into the nature of sleep paralysis, you’ve come to the wrong filmmaker, just as anyone looking for commentary about The Shining would be better served outside of Room 237. Hell, you’d be better off watching an episode of Unsolved Mysteries, because you’d at least get the soothing voice of Robert Stack gracing your obviously tired ears. But it’s never been about the reality, it’s been about the experience. How do a myriad of people interact with and differently remember the same event, the same piece of art, the same psychological phenomenon? The ways their interpretation of a thing- whatever that thing may be- changes depending on their background is what we’re really meant to look at. How can two people see The Shining as a metaphor for the holocaust and the genocide of native Americans? What are the similarities? How can the same source material give us two very different readings?

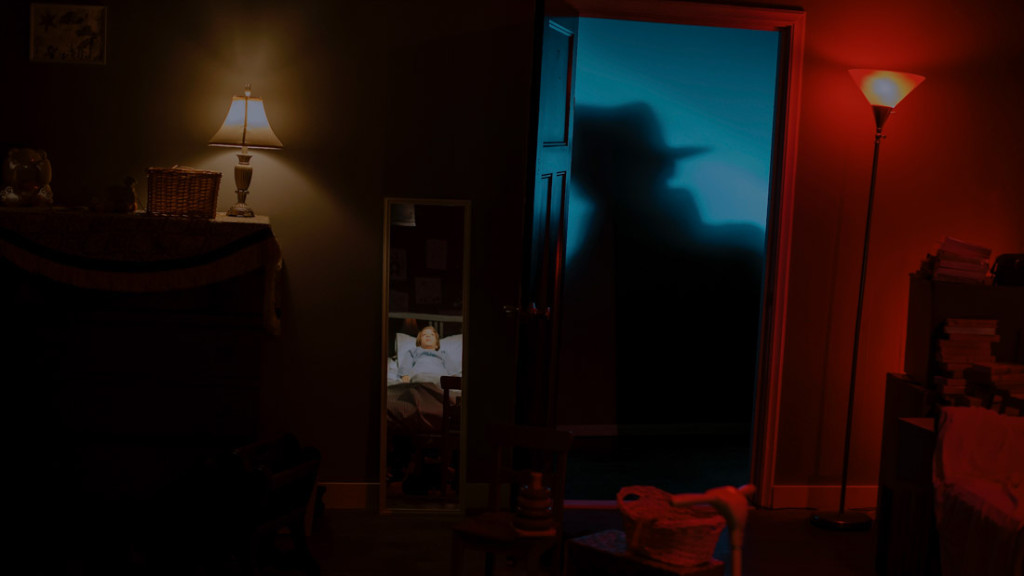

In the same way, The Nightmare asks us to consider how sleep paralysis stays constant and changes between people, not whether what they’re experiencing is “real” or “true”, but whether what they have gone through matches up with other people, whether it’s reoccurred. The reenactments we see of these events aren’t “scary” because they are documents of the truth, but because they are documents of a reality, and they show what one person really experienced. After all, does it really matter if shadow people came into a child’s bedroom or if the child just imagined it? Of course not, because the memory and the event is the same. It left the child shaken for the rest of their life. What we experience is what matters, at the end of the day – not the “objective” world, but subjective memory, subjective sensations. You can tell yourself all day that the walking, talking alien whose skin looks like television static isn’t real, but when you see it, it might as well be. There’s no judgement, no cruelty, and no wink-wink nudge-nudge editing or cinematographic tricks to make the people who have experienced this terror look silly, or to discount them, just an attempt to relate an experience.

If there’s any issue to be had with the film, it’s that in comparison to its predecessor, Room 237 (one of the best documentaries of the emerging decade), its subjects experience realities that are too similar. Where Room 237 gave us a panoply of opinions, The Nightmare dives deep into one experience, and throughout its different subjects keep a narrative constant. There’s reasons for this; the human nervous system has developed in a way that many of these hallucinations will inevitability be the same. Shadow people with red eyes are artifacts of the glitches in the brain, and as such their nature stays constant through most of the witness testimony. But the pull of this singular experience pushes through the somewhat same-y nature of the recollections, and the audience truly feels the fear of sleep paralysis, the fear of sleep, the fear of the reduction of control, of the reduction of consciousness.

Ultimately, this fear is what makes the documentary worthwhile. Ascher is the best horror filmmaker today not working in horror film. He sets up a situation, asks people to explain it, and the myriad of explanations (and the connecting threads between them) becomes the horror. It’s no small coincidence that knowledge of sleep paralysis increases one’s likelihood of experiencing sleep paralysis; Rodney Ascher is infecting his viewing audience with knowledge, with subjective reality, and maybe he even hopes that the viewer experiences what he’s worked so hard to describe. If the viewer goes to sleep worrying that the same thing might happen to them, then he’s done his job, regardless of what anyone might claim. What scares us is the unconscious, and the reality therein; when what we experience correlates with the reality of what can hurt us, our safety falls away, and we are left with nothing but a shadow, a man in a hat, red eyes staring out from the darkness of our homes.

—

The Nightmare is now playing in select theatres.

Directed by Rodney Ascher; 91 minutes.

Derek

Derek

Isabelle

Isabelle