If there was one film released in 1966 that captured the zeitgeist of 1966, you’d be hard pressed to find a better candidate than Blow-Up. With its swinging-Sixties London setting, celebration of promiscuous sex and triple lacquer of fashion, photography and music, Michelangelo Antonioni’s first English-language picture went on to be representative of all things counter-culture. But unlike, say, Easy Rider, Blow-Up is not merely a document of its time that seems to lose relevance and power with every passing year. Now celebrating its 50th anniversary, Antonioni’s film still stands as a striking splash of pop and high-art that is as ambiguous as it is satisfying.

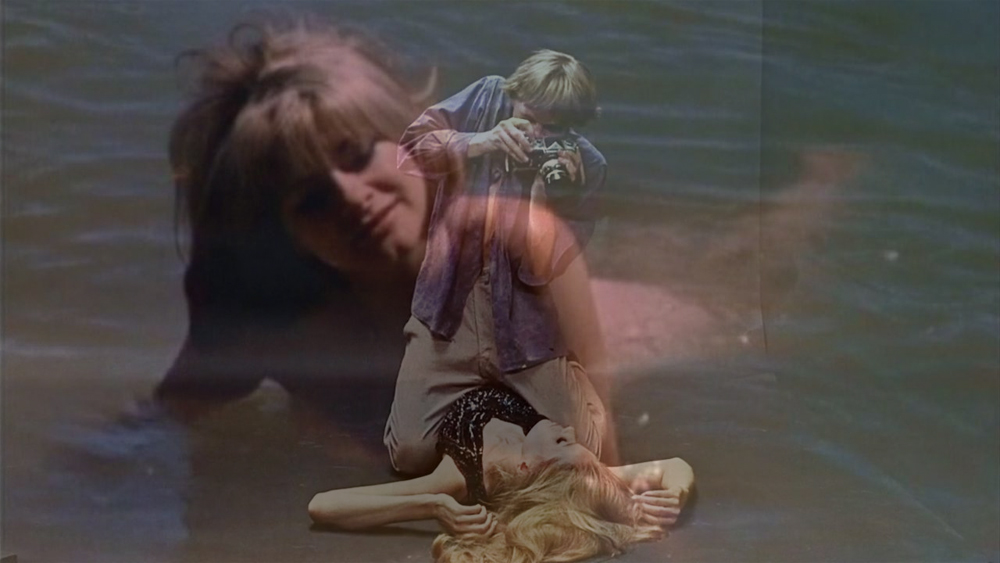

David Hemmings plays Thomas, an in-demand photographer who becomes convinced he has unwillingly captured a murder in one of his photos. In one of the film’s signature scenes, Hemmings continuously blows up one of his prints to determine whether or not the hazy shadow causing him so much stress is a dead body or a mere trick of light. Instead of a definitive answer, however, he is faced with nothing but an increasingly equivocal blur. The film never answers the question central to its mystery despite presenting us with seemingly damning evidence; a panicked Vanessa Redgrave, the wife of the suspected deceased, shows up at Thomas’ studio begging for the camera negative and many other suspicious signifiers but Antonioni is less concerned with the whodunnit than the where and when.

As evident from his groundbreaking Italian films like L’avventura, La notte, and L’eclisse, Antonioni was always a master of environment and atmosphere. So much of Blow-Up’s impact comes from the sound and vision surrounding the characters as well as the time and place. Sixties London is beautifully explored during Thomas’ numerous excursions from the studio. Whether it’s watching him drive around with an antique propeller in the back seat of a convertible or impulsively crashing an early Yardbirds gig, the film never misses an opportunity to lay a finger on the 60s pulse rendered in glorious primary colors. For all the activity surrounding Thomas, he never seems fulfilled. He floats through Blow-Up searching for a moment to capture with his camera or inspiration to strike. He fights off a hungry crowd at the Yardbirds gig for the broken neck of Jimmy Page’s guitar only to toss it in the gutter minutes later. He enjoys sexual escapades with young models but loses interest once they cease to be mysterious. It is only when he stumbles upon a potential murder that he finally finds a purpose, even if that too leads to nothing but an enlarged photograph hanging aimlessly in his studio.

Antonioni’s films constantly pushed the boundaries of narrative filmmaking and eschewed conventional storytelling tropes in favor of those exclusive to cinema. Antonioni’s plots, if you can call them that, never climaxed in resolution and finality for the characters but rather progressed deeper into the form of film itself to find deeper meaning. At the end of Blow-Up, Thomas doesn’t get the answers he’s looking for, instead he stumbles upon a couple playing tennis but there is no ball to be seen. As the imaginary ball lands at his feet, he joins in the charade and tosses it back to the couple. Thomas walks away as the game continues, only now the sound of the ball bouncing on concrete can clearly be heard on the soundtrack. The message? Everything is an illusion.

Like most of the great art to emerge in the 1960s, Antonioni’s work was fresh rather than familiar and tended to set trends rather than follow them, which brings us nicely to the opposition in this round of the Tournament of Films: Russ Meyer’s Mondo Topless!

Russ Meyer’s first color film kicks off with (what else?) endless shots of busty babes flaunting their mammaries to the sound of an aggressive narrator who announces:

Mondo Topless is believably real in Eastman Color. But unbelievable just barely describes all of Russ Meyer’s discotheque discoveries. Fantastic women, fantastic dancers, featuring the worlds loveliest buxotics, you only dreamed there were women like these until now. But they’re real, unbelievably real in Mondo Topless!

Mondo Topless is less a film than it is a montage of tits and ass posing as a pseudo-documentary. Meyer made the film hoping to cash in on the sudden interest in free love following a string of financial failures. Clocking in at a mere 60 minutes and featuring little more than episodes of women dancing topless accompanied by voice over, it’s an incredibly slight and tiresome exercise in soft-core nudie filmmaking.

I imagine the great pleasure of watching Mondo Topless in 1966 was sitting in a sleazy movie theatre and jacking off to your heart’s content before walking out when done. You might even use it as background projection at an orgy. The thing is, watching Mondo Topless in 2016–where the Internet and endless free porn are things and softcore nudity is a thing of the past–it’s kind of redundant. I can appreciate a good pair of breasts as much as anyone but watching them rotate and bounce endlessly for an hour just isn’t enough to sustain my interest.

Even as a showcase for Russ Meyer’s talent, Mondo Topless a failure. Despite his reputation as King of the Nudies, Meyer was actually an incredibly distinctive and gifted filmmaker. William Goldman once named Meyer, who wrote, produced, directed, shot and edited his films, as “the one true Auteur in American cinema”. And sure enough, if you were to look at films like Beyond the Valley of Dolls, Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, Lorna and Mudhoney you will see an unmistakable vision at work. Gonzo plotting, inspired editing and unforgettable characters lie at the heart of Meyer’s best work. Very little of that, beyond Meyer’s knack for restless montage, is on display in Mondo Topless.

The film does have a certain kitschy charm though. The playful celebration of the fuller female form and harmless titillation is oddly sweet in this day and age. The sexuality feels fluffier and more enjoyable than Blow-Up which is very cold and cruel to its female characters. Like Blow-Up, Mondo Topless feels like a film very much of its time, but while Antonioni refused to merely give his audience what they wanted, Meyer was more than happy to oblige their perverse fantasies with endless flesh on show. It should come as no surprise then that one of those films has faded into almost total obscurity while the other continues to be a mini-touchstone.

Even if you’ve never seen anything from Blow-Up aside from the iconic one-sheet on Spider-Man’s bedroom wall, chances are you’re familiar with its never-ending influence. Francis Ford Coppola and Brian De Palma famously lifted plot elements wholesale for their audio-focused riffs The Conversation and Blow Out while Mike Myers squeezed three Austin Powers send-ups out of its imagery and attitude. While it’s contemporary influence and importance might have receded over the years, it remains a key text in film history and a gateway film for many people discovering Antonioni or arthouse cinema from this era in general. Meanwhile, Russ Meyer made many memorable movies in his lifetime but sadly Mondo Topless is just not one of them.

The winner: Blow-Up

—

Blow-Up; directed by Michelangelo Antonioni; written by Michelangelo Antonioni, Edward Bond, and Tonino Guerra; starring David Hemmings, Vanessa Redgrave, Sarah Miles; 111 minutes.

Mondo Topless; directed by Russ Meyer; starring Babette Bardot, Pat Barrington, and Darlene Gray; 60 minutes.

Derek

Derek

Isabelle

Isabelle