Crash turns twenty years old this year. Even today David Cronenberg’s controversial adaptation of JG Ballard’s equally controversial novel feels like an earth-shattering breakthrough in depicting sex in movies. Sex can be weird, kinky, scary, confusing, touching, hilarious, experimental, awkward, arousing etc., etc. It’s pretty bizarre how movies and the media have programmed us to see sex as a shocking and provocative act. Of-course it can be that but for the most part sex is just a natural ingredient of every-day life. We’re much more comfortable seeing an entire planet blown to smithereens in fiction than we are watching a couple have explicit sex. Isn’t that just fucking crazy? I often wonder if we’ll get to a place where that balance shifts and nudity, sensuality and intercourse are more accepted and embraced than mindless violence. If that day comes, then Crash will be seen as a movie wayyyyy ahead of it’s time. It is a breakthrough in narrative filmmaking that often goes un-recognized but it’s as bold a statement in cinema as anything I’ve seen.

The thing is: no filmmaker alive understands, appreciates and dissects the human body like David Cronenberg. I’ve thought about this director a lot over the past few years (due to many of his works getting lavish special edition treatments on home video) and I’m often inclined to name him the greatest who has ever lived. If just for the fact that he seeks out truths and imperfections so many other filmmakers completely ignore or obscure. He isn’t afraid of the icky or the perverse but his clinical directing style heightens these moments from mere titillation and exploitation. They become enlightening and thrilling. One of the most important close-ups in Crash is of a quivering hand covered in semen. How many other American filmmakers would even dare depict that moment on-screen let alone use it as the culmination of a character’s emotional journey. In 1996 no less! You see, Cronenberg uses the sex scenes in Crash as an alternative to dialogue or loaded glances between actors. The film speaks its own language: it is told through the sex.

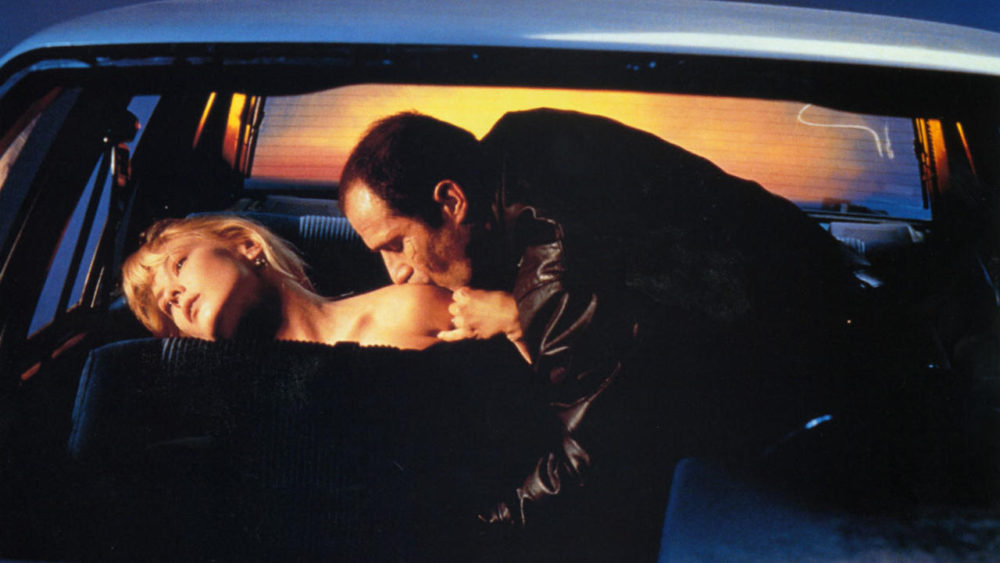

Almost everything we know about the characters in Crash we learn from watching them fuck. It’s jarring at first–the film is essentially a string of loosely connected sex-scenes–but as soon as you get past blushing like a prude and pay attention, you realize that all of this has a point. Whoever choreographed these sex-scenes should have been up for some kind of award because even the positions the characters choose tell us something about their mindset. Most of the sex is done from behind and the only sex that happens face-to-face is the sex that means something for them on an emotional level. Working with regular DP Peter Suschitzky, Cronenberg stages many of these scenes in long takes, letting the sex build and unfold in front of us free of cuts. We become voyeurs and, like the characters, we learn to become numb to the nudity and enjoy its deeper significance. These characters love sex, they enjoy exploring their bodies and pushing it into new directions and aren’t ashamed of it. The film isn’t ashamed of it either. Cronenberg never judges these people. We might not relate to their desires but the film never goes out it’s way to depict these characters as weird or their lifestyle as wrong. It’s a choice. Crash is an exploration, not a damnation. I love that about it. It’s what I love about Cronenberg’s entire career. His ethos? Weird is the new normal.

No matter how unusual or taboo a topic, Cronenberg always treats it with respect, intelligence and balance. You get a sense that he has as much understanding and sympathy for the diseases in Shivers and Rabid or the body-horror phenomena in The Brood, Scanners, Videodrome and The Fly as he does for the victims who fall afoul of them. The character of Vaughan (Elias Koteas) in Crash definitely has a sinister air about him and is the closest thing the film has to an antagonist but, like Ballard (James Spader and the author of the source material; JG), the film is fascinated by him. As Ballard and his wife Catherine (Deborah Kara Unger) fuck in one scene, she tells him to picture intimate details of Vaughan’s scarred body and asks him if he thinks about “fucking his anus” or if the scars cover his penis. This is dirty talk, yes, but we soon find ourselves wondering the same thing about Vaughan. He infects every scene he isn’t in and his mystique can be overwhelming. Crash was so controversial at the time of release that many forgot to consider the quality and bravery of these performances and Koteas especially is on another level. Granted, it is the showiest role in the ensemble but his silhouette–the dirty overalls, the mangled crash scars covering his pale skin–is the perfect visual embodiment of Crash‘s identity.

It’s been a long, long time since I saw Crash before writing this piece and, while I have always considered it a masterpiece, this time around I found its impact even more potent. This might be the first time I’ve revisited it since losing my virginity and I wonder if that has anything to do with it. Maybe having more experience with sex first-hand and understanding how it can be as much a form of communication as well as a physical act made me find greater appreciation for it. Then again, maybe not.

Not only does Crash challenge and provoke you in unconventional ways but it takes the very concept of sex-scenes in cinema and re-configures them to be something more than raunch or unrealistic physical acrobats. They are completely integral to this world, the characters’ lifestyle and the how the story is told. I think Crash failed to catch on with so many people because they just weren’t ready to look past the explicitness and actually think about it’s purpose. The shock-value is there: it’s a movie about people getting aroused by car-crashes, James Spader fucks a wound in Rosanna Arquette’s leg, but the intelligence is there too. As with many Cronenberg movies, it might look and feel like a lot of cold surfaces–even Howard Shore’s sublime score sounds like the aural equivalent of streetlights bouncing off of vehicular steel–but Cronenberg’s scalpel-like dissection eventually draws real blood. The result is a movie that tackles sexuality unlike anything else made before or since (it is also more inclusive than much of today’s sex-themed movies, the distinction between homo and heterosexuality is non-existent.) Even now, twenty years after it’s release, no other filmmaker has dared to make an English-language equivalent. Crash will scare, educate, arouse you in ways you never thought possible and introduce you to concepts you may find unwholesome (in short: quintessentially Cronenbergian). But isn’t that the purpose of all great art? I hope one day mainstream audiences will catch up and agree.

—

Directed by David Cronenberg; written by David Cronengberd; based on the novel by J.G. Ballard; starring James Spader, Deborah Kara Unger, Elias Koteas, Holly Hunter, and Rosanna Arquette; 100 minutes.

Derek

Derek

Isabelle

Isabelle