Speaking in cinematic terms, the ’80s remain a patchy region in my own cultural map. I’ve seen neither Ferris Bueller’s Day Off nor any Back to the Future film, but I did grow up with Indiana Jones. For a period of time in my childhood, Top Gun was my favorite film, its soundtrack my favorite CD. Labyrinth was, strangely, the first movie I ever saw on DVD. All of this is not simply a disclosure of my personal history. This is an acknowledgement of the crucial fact that I can only experience the ’80s as it is understood by and refracted through the following decades, as a discrete historical category granted a beginning and an end. Before I was able to understand and consider how the ’80s had shaped the decades of my life, I first felt how the ’80s were remembered and reshaped—hence Labyrinth seen first on DVD.

So why begin this way, dilly-dallying with history and nostalgia? Because, with Christopher Nolan’s own Batman franchise (The Dark Knight especially) occupying such a monolithic presence in Batman’s cinematic pedigree, and with Zack Snyder’s Batman v Superman as of now rumbling on the horizon, I find it very difficult to talk about Tim Burton’s Batman without acknowledging how it is remembered and how it has shaped the ways we’ve come to view Batman and all superhero films on the big screen.

At its time, Burton’s Batman was a dark and serious take on the hero—this is coming after the camp of the 60s Batman TV series, which seems to be remembered these days largely for its stark contrast with the gravity of the modern Batman. Viewing Burton’s film from a moment when Batman grows grittier with every cinematic reinterpretation, however, one thing is overwhelmingly apparent: how fun it is. By fun, I don’t mean necessarily its entertainment value (though entertaining it certainly is). I mean its playfulness, how willing it is to embrace drastic shifts in tone—humor and horror and requisite Bruce Wayne brooding. I mean its investment in genre, I mean the imaginative art direction.

Michael Keaton makes a fine Batman. The gravelly register his voice inhabits while he wears the mask is now classic. His naturally comedic body language lends itself to a Bruce Wayne who is unsure of who he is outside of the suit, uncomfortable speaking to anyone except Alfred. His fight choreography is inflected with the same physical comedy, though this might only be because the costume doesn’t allow him to move his neck. But the problem with this iteration of Batman is that his characterization relies heavily on the audience’s familiarity with the character; he often feels more like an archetype than a character with serious depth. Only two characters in Batman demand the viewer’s attention with bracing urgency: the Joker, played by Jack Nicholson, and the setting of Gotham itself.

In 2008, Heath Ledger’s Joker in The Dark Knight came to be regarded as a high water mark for both acting in superhero films and the late actor’s career. Much of this praise comes, directly or indirectly, in the form of comparison to Nicholson’s interpretation of the character, and for this reason, it’s difficult for me to watch Nicholson and not take note of all the traits which form points of departure for Nolan and Ledger. He inhabits the role of a joker in a literal way, delighting himself with wordplay and homicidal pranks, while the name “Joker” for Ledger’s character is hardly more than a bitterly ironic title, doing away as he does with gag buzzers and balloons for knives and bombs. Nicholson’s Joker aligns himself with the societal avant-garde and fancies himself more of an artist than a terrorist—one of my favorite scenes in the film is his vandalism of the art museum, splashing paint on classical works but sparing the disturbingly modern Francis Bacon painting Figure with Meat, itself a vandalistic appropriation of Diego Velázquez’ portrait of Pope Innocent X. He speaks of liberation through death, and his form of chaos (for that is what the Joker, as the foil to Batman’s monomaniacal fixation on order and justice, represents) is the upheaval of the present social order rather than the outright dissolution of all society, in contrast to Ledger’s Joker.

Nicholson is a consummate performer, an actor whose presence is all but impossible to ignore. His Joker is as disturbing as he is funny; it’s difficult to imagine any other actor of the time not just inhabiting but revelling in such a mercurial character. But every performer needs a stage on which to stand, and for Nicholson’s Joker, that’s Gotham City. Burton’s take on the metropolis, rendered in that cartoonishly twisted style that can only be called Burtonesque, is not so much tinged as suffused with the trappings of film noir: bought-off police officers in fedoras and trenchcoats, Art Deco architecture, steam rising through grates. He’s created a world which appears to be technologically modern but ideologically and aesthetically stuck in the past—even as the Joker dances to Prince. There’s a hefty essay to be written about the societal orders against which Burton’s and Nolan’s Jokers react, and the real-world conditions of which these fictional worlds are symptoms, but I am not the person to write it—not least of all because I still have another movie to write about.

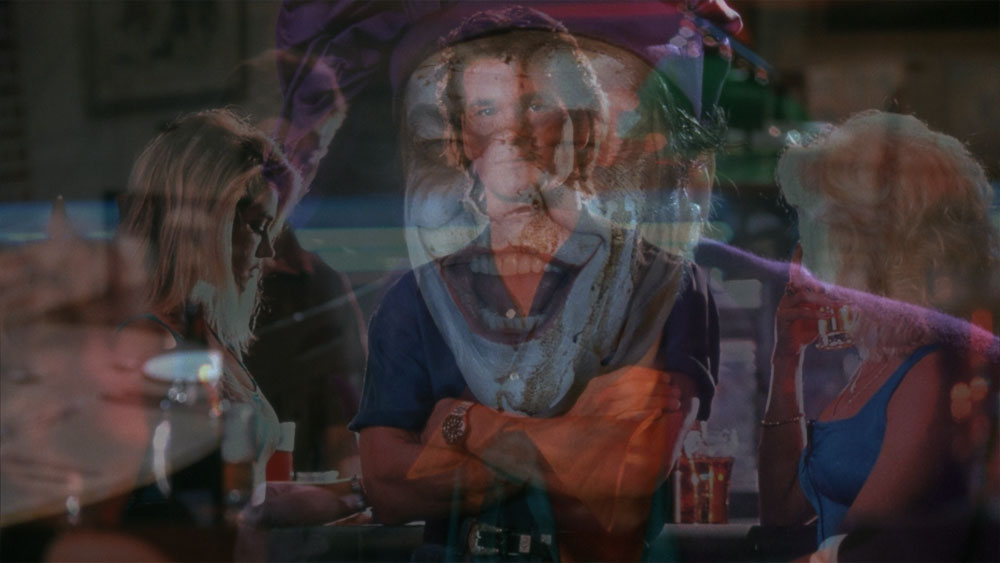

Patrick Swayze as Dalton is something of a Batman figure in Road House, if you squint and look at him the right way. He’s a mythical enforcer of order and justice, a vigilante haunted by a dark past, a troubled man who struggles to keep himself in line with his own code of ethics. He’s the greatest “cooler” of his generation, though how a “cooler” is distinguished from any old bouncer is not explained to the layman. Dalton’s Gotham is the Double Deuce, a small-town Missouri bar where the town troublemakers and ne’er-do-wells congregate to deal drugs, brandish knives, and smash bottles on floor and flesh alike. Dalton is the bar’s bulwark against the forces of entropy, and indeed, he excels at his job, for exterior and interior shots throughout the film show the bar’s transformation from sawdust-coated saloon to a hip and happening club, the clientele growing younger and cleaner.

While Batman revels in Keaton and Nicholson’s tonal whiplash, Road House seems genuinely unsure what reaction it wants to elicit from the audience. The action sequences are a given—they’re there to get your blood pumping—but even in these scenes the film will trip over its own feet by, for example, having Swayze flatly deliver a hammy one-liner mere seconds before ripping out a man’s throat. Violence and nudity alike erupt out of nowhere only to dissipate with little influence on the film’s trajectory. Frequently a serious scene will end abruptly with a tonally jarring musical cue delivered by Jeff Healey and his band (I will take this opportunity to note how excellent the movie’s blues-rock soundtrack is). There’s one sequence where a car dealership is demolished by a monster truck and in another, Patrick Swayze, bare chest glistening, does Tai Chi at sunset. The list goes on: it’s unclear when the film wants you to say “hell yes” or “oh my God,” and that’s its main appeal—besides Sam Elliott, whose dynamic and effortless charisma far outshines Swayze everytime the two men share the screen.

This is why I began this piece as I did: a film like Road House is difficult to watch at this moment as anything less than a quintessentially “’80s” film, a category which can only be applied to it retroactively. It seems to wink at the modern viewer all while playing off its absurdities with a straight face; it seems made to be half-watched in a frat house living room. It’s an entertaining movie through and through, even if the avenue by which one reaches that entertainment depends on perspective. I enjoyed myself no less watching Road House than I did Batman, even if I scoffed and snorted almost the whole way through the former. The reason I choose Batman to continue to the next round is thus: it remains in conversation with present-day films, for its influence is still felt today as the superhero film becomes a genre unto itself. Road House, fun as it is, is stuck in a quagmire of ’80s novelty, to be dredged up only as a quaint excursion into the past.

The winner: Batman

—

Both films are available for purchase on Amazon and from rent through Netflix and/or your local independent video store.

Batman; directed by Tim Burton; written by Sam Hamm and Warren Skaaren; starring Michael Keaton, Jack Nicholson, Kim Basinger, Robert Wuhl, Billy Dee Williams, and Michael Gough; 126 minutes

Road House; directed by Rowdy Harrington; written by David Lee Henry and Hilary Henkin; starring Patrick Swayze, Kelly Lynch, Sam Elliott, and Ben Gazzara; 114 minutes

Derek

Derek

Isabelle

Isabelle